When your skin starts to tighten so much that you can’t fully open your fingers, or your fingers turn white and blue in the cold, it’s easy to brush it off as just being sensitive to the weather. But for more than 300,000 Americans, these aren’t minor quirks-they’re early signs of scleroderma, a rare and progressive autoimmune disease that attacks connective tissue from the inside out.

What Scleroderma Really Is

Scleroderma, also called systemic sclerosis, isn’t just a skin condition. It’s a systemic autoimmune disorder where your immune system mistakenly triggers excessive collagen production. Collagen is normally a building block for skin and tissues, but in scleroderma, it piles up like concrete, hardening skin, blood vessels, and even internal organs. The name comes from Greek: sclero means hard, and derma means skin-but the disease goes far beyond the surface.

There are two main types. Localized scleroderma affects only the skin, often in patches, and doesn’t spread to organs. Systemic scleroderma is the more serious form. It can involve the lungs, heart, kidneys, and digestive tract. About 90% of systemic cases involve the gastrointestinal system-leading to severe heartburn, trouble swallowing, or bloating that feels like constant indigestion. Around 80% develop lung scarring (pulmonary fibrosis), and 30-45% face heart complications.

Who Gets Scleroderma and Why

Scleroderma doesn’t pick favorites, but it does have patterns. Most people are diagnosed between ages 30 and 50. Women are four times more likely to develop it than men. While no single gene causes it, having a family history slightly increases risk. Environmental triggers-like exposure to silica dust, certain solvents, or viral infections-may turn on the disease in people with a genetic predisposition.

One of the clearest clues is the presence of antinuclear antibodies (ANA). Over 95% of systemic scleroderma patients test positive for ANA. But the real diagnostic power comes from specific autoantibodies:

- Anti-Scl-70 (Topoisomerase I): Found in 30-40% of diffuse cases. This type often means faster skin thickening and higher risk of lung fibrosis.

- Anti-centromere (ACA): Seen in 20-40% of limited cases. These patients usually have slower progression and lower risk of major organ damage.

- Anti-RNA polymerase III: Present in 15-25%. This one is linked to rapid skin changes and a higher chance of developing cancer alongside scleroderma.

These antibodies aren’t just markers-they help doctors predict how the disease might unfold.

The Silent Warning Signs

Most people don’t wake up one day with hardened skin. The disease creeps in slowly. Raynaud’s phenomenon is the earliest red flag-in 90% of cases, it shows up 5 to 10 years before anything else. Your fingers or toes turn white, then blue, then red when exposed to cold or stress. It’s not just cold hands; it’s a sign your small blood vessels are spasmming and getting damaged.

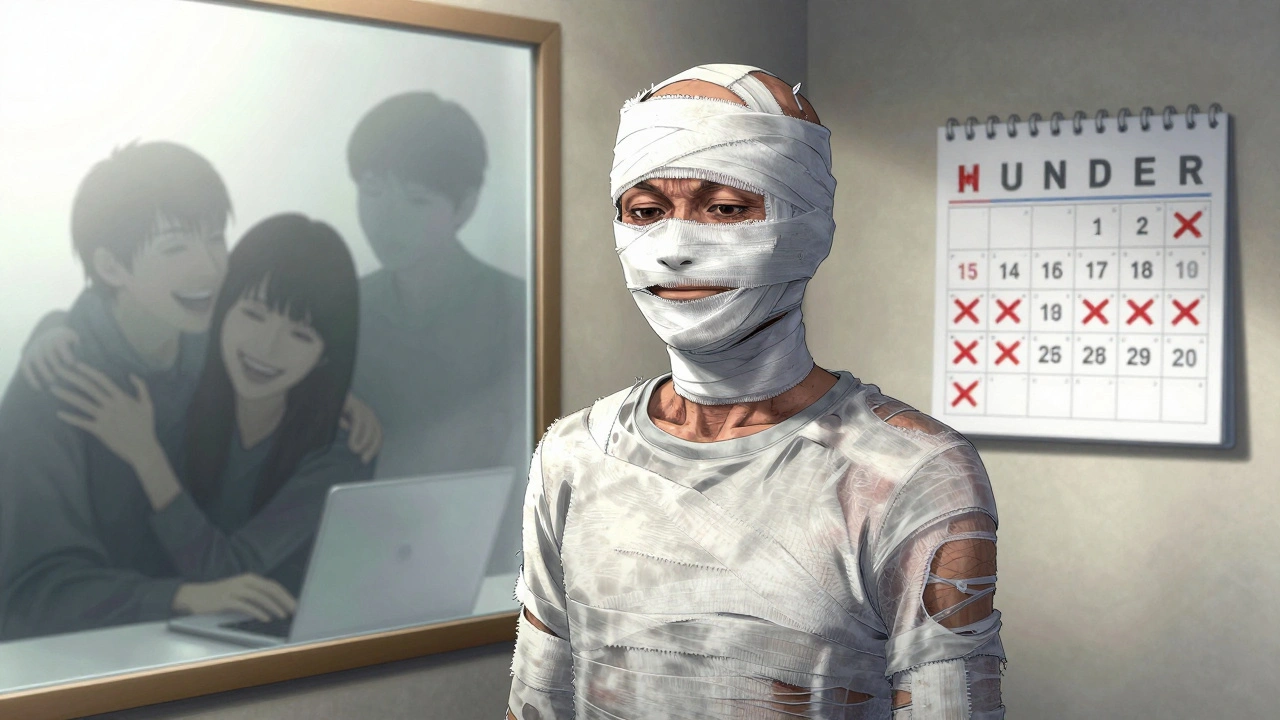

Soon after, skin changes begin. Fingers swell, then stiffen. You can’t make a full fist. This is called sclerodactyly. It affects 95% of systemic cases. The skin on your face tightens too, making it hard to smile wide or open your mouth fully. Some people describe it as feeling like they’re wearing a suit made of shrink-wrap.

Other early signs include persistent fatigue that doesn’t improve with rest, unexplained weight loss, and digestive issues like acid reflux that won’t respond to standard antacids. Many patients spend years going from doctor to doctor-seeing a dermatologist for skin changes, a gastroenterologist for reflux, a cardiologist for shortness of breath-before someone connects the dots.

How It Compares to Other Autoimmune Diseases

Scleroderma is often confused with lupus or rheumatoid arthritis, but the differences matter.

Lupus causes joint pain and rashes from inflammation. Scleroderma causes joint stiffness from skin tightening. Rheumatoid arthritis attacks joints directly, leading to swelling and erosion. In scleroderma, joints are stiff because the skin around them has turned to rubber. Polymyositis weakens muscles. Scleroderma doesn’t primarily attack muscle-it attacks the connective tissue that holds everything together.

And unlike lupus, which affects about 1.5 million Americans, scleroderma is far rarer-only about 19,000 new cases each year. But its impact is deeper. While lupus flares can be managed with steroids, scleroderma’s fibrosis-the actual scarring of tissue-is irreversible. Once lung or heart tissue is scarred, it doesn’t heal.

Why Diagnosis Takes So Long

On average, patients see 3.2 different doctors over 18 months before getting a correct diagnosis. Why? Because early symptoms are vague. Fatigue? Common. Heartburn? Almost everyone gets it. Cold fingers? Probably just winter.

Doctors who don’t specialize in autoimmune diseases rarely see scleroderma. A general rheumatologist might see one or two cases a year. Specialists at centers like Johns Hopkins, Stanford, or the University of Michigan see dozens. That’s why patients who get care at dedicated scleroderma centers report 68% better symptom control compared to those treated by general practitioners.

Early diagnosis isn’t just about labeling-it’s about catching organ damage before it’s too late. Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), a deadly complication, can develop silently. Regular echocardiograms every 6-12 months are critical. If caught early, PAH can be managed with medications like endothelin receptor antagonists or phosphodiesterase inhibitors.

Treatment: What Works, What Doesn’t

There’s no cure. And there are no FDA-approved drugs designed specifically to stop scleroderma’s fibrosis. Most treatments are borrowed from other diseases.

Immunosuppressants like mycophenolate or cyclophosphamide are used to slow down the immune attack. But studies show only 40-50% of patients get meaningful relief. Even then, these drugs don’t reverse scarring-they just try to slow it down.

The biggest breakthrough came in 2021 when the FDA approved tocilizumab for scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease. It’s the first drug ever approved specifically for this complication. It doesn’t fix the skin, but it can slow lung decline in some patients.

For Raynaud’s, calcium channel blockers like nifedipine are standard. For digital ulcers (open sores on fingers), iloprost infusions help open blood vessels-but they’re expensive and often denied by insurance. For severe cases, some patients qualify for autologous stem cell transplants. The 2023 SCOT trial showed 50% improvement in skin scores at 54 months for those who underwent the procedure.

But access is uneven. Only 35% of U.S. scleroderma patients get care at one of the 45 designated centers of excellence. That means two-thirds are treated by doctors who may not know the latest protocols.

Living With Scleroderma: Daily Realities

It’s not just medical-it’s life-changing.

Seventy-eight percent of patients say hand contractures make daily tasks like buttoning shirts, opening jars, or typing impossible without adaptive tools. Sixty-five percent use special utensils, grip aids, or electric jar openers. Sixty percent develop painful digital ulcers that require weekly wound care visits.

Eighty-two percent have GI issues. Many eat small, frequent meals. Some avoid lying down after eating. Others need multiple medications daily-proton pump inhibitors, prokinetics, laxatives-to keep digestion moving.

Fatigue hits 70%. Not the kind you can sleep off. This is deep, bone-tired exhaustion that makes working, parenting, or even showering feel overwhelming.

And then there’s the emotional toll. Eighty-five percent of patients say they felt dismissed or misunderstood before diagnosis. Many report anxiety over the unknown-will their lungs fail? Will their heart give out? Will they lose the ability to hold their grandchild’s hand?

The Future: Hope on the Horizon

Research is accelerating. The Scleroderma Research Foundation committed $15 million in May 2024 to target fibrosis pathways. There are 47 active clinical trials-15 testing B-cell therapies, 12 looking at tyrosine kinase inhibitors for lung disease.

A new blood biomarker, serum CXCL4, shows promise for earlier diagnosis-possibly before skin changes even appear. Stanford’s telemedicine program, launched in January 2024, is helping rural patients get specialist care via monthly video visits. Preliminary results show a 32% drop in hospitalizations.

And as people live longer with scleroderma-thanks to better monitoring and treatments-the population is aging. Johns Hopkins predicts a 40% increase in patients over 65 by 2030. That means managing scleroderma alongside diabetes, heart disease, and arthritis will become the new normal.

What You Can Do

If you’ve had Raynaud’s for years and now notice stiff fingers, unexplained fatigue, or worsening reflux, don’t wait. Ask your doctor about scleroderma. Request an ANA test and ask if you should be referred to a rheumatologist who specializes in connective tissue diseases.

Track your symptoms: keep a log of Raynaud’s episodes, skin tightness, digestion, and energy levels. Bring it to appointments. Bring someone with you. Ask questions. Demand a referral if you’re not getting answers.

Scleroderma is rare, but you’re not alone. Support groups, patient registries like SPIN, and specialized centers offer real help. Early action doesn’t guarantee a cure-but it can mean more years with your hands, your lungs, and your life intact.

Rupa DasGupta

4 Dec 2025 at 18:42I’ve had Raynaud’s since I was 12 and now my fingers look like little sausages 😭 I’ve been told it’s just ‘cold sensitivity’ for 15 years. Finally got diagnosed last year. Scleroderma isn’t a phase. It’s a life sentence. And no, I don’t want to ‘just warm up’.