Dyskinesias: What They Are and How to Deal With Them

If you’ve ever seen someone with jerky, uncontrollable motions, you’re probably looking at dyskinesias. These are unwanted, involuntary movements that can affect the face, limbs, or whole body. They aren’t a disease themselves but a symptom that pops up when certain brain pathways get out of sync, often because of medication or neurological conditions.

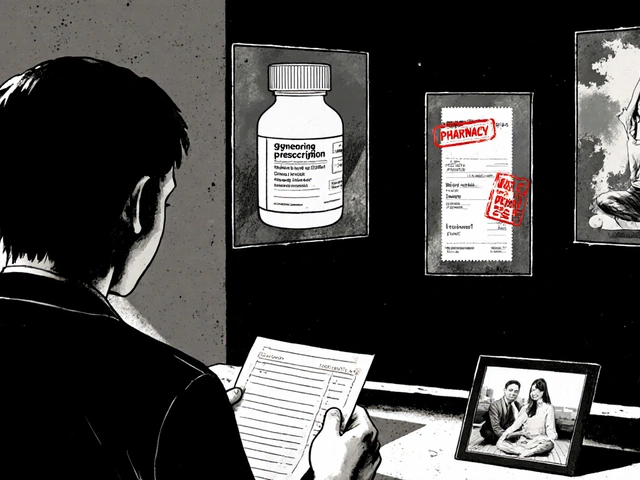

Most people first hear about dyskinesias in connection with Parkinson’s disease. The drugs used to boost dopamine—like levodopa—can wear off the brain’s balance and cause these twitchy motions. But they don’t stop at Parkinson’s; antipsychotics, anti‑emetics, and even some antidepressants can trigger similar side effects.

Common Causes of Dyskinesias

The biggest culprit is dopamine‑related medication. When the brain receives too much or fluctuating dopamine, it overreacts, sending out erratic signals that turn into shaking, writhing, or repetitive gestures. Long‑term use of levodopa in Parkinson’s patients often leads to “peak‑dose” dyskinesias, which hit strongest when drug levels are highest.

Other triggers include:

- Antipsychotics: especially older, high‑potency ones like haloperidol.

- Anti‑nausea meds: drugs such as metoclopramide can mess with dopamine pathways.

- Genetic factors: some people inherit a higher risk of drug‑induced movement disorders.

Sometimes the cause is unclear—these are called idiopathic dyskinesias. They might appear after head injuries or in rare metabolic conditions, but they’re less common than medication‑related cases.

Managing and Reducing Symptoms

The first step is a honest conversation with your doctor. Adjusting the dose, switching to a different drug, or adding a dopamine‑blocking agent can calm the unwanted movements. For Parkinson’s patients, using extended‑release formulations or combining levodopa with a catechol‑O‑methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitor often smooths out peaks and valleys.

Physical therapy also helps. Targeted exercises improve muscle control, while techniques like deep breathing can lessen the intensity of tremors during stressful moments. Some people find relief with non‑pharmacological tricks—wearing weighted gloves, using a stress ball, or simply pausing to relax the affected muscles.

If meds aren’t enough, doctors might consider surgical options such as deep brain stimulation (DBS). DBS delivers mild electrical pulses to specific brain regions, reducing both Parkinson’s symptoms and medication‑induced dyskinesias for many patients.

Finally, lifestyle tweaks matter. Adequate sleep, balanced nutrition, and staying hydrated keep the nervous system stable. Avoiding caffeine or alcohol before taking dopamine meds can also prevent sudden spikes that lead to twitchy episodes.

Living with dyskinesias isn’t easy, but understanding why they happen gives you tools to fight back. Talk to your healthcare team, explore therapy options, and keep track of what makes the movements better—or worse. With the right approach, those involuntary motions can become manageable rather than overwhelming.

In my latest blog post, I delved into the intriguing link between dyskinesias, involuntary muscle movements, and sensory processing disorders. I discovered that individuals with dyskinesias often experience sensory processing issues, as both conditions are rooted in the malfunctioning of neural pathways. This connection can result in challenges with movement coordination and processing sensory information. However, therapies targeting sensory integration can be beneficial for both conditions. This fascinating connection underscores the complexity of the human brain and the interconnectedness of its functions.