When your heart muscle doesn’t work right, it doesn’t just feel like fatigue-it can stop your body from getting the blood it needs. Cardiomyopathy isn’t one disease. It’s a group of conditions that change the structure and function of the heart muscle, and the three main types-dilated, hypertrophic, and restrictive-each behave in very different ways. While they all lead to heart failure over time, how they develop, who gets them, and how they’re treated are completely different. Knowing the difference isn’t just academic; it can mean the difference between life and death.

Dilated Cardiomyopathy: The Heart That Grows Too Big

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is the most common type, making up about half of all cardiomyopathy cases. Imagine your heart’s main pumping chamber, the left ventricle, stretching out like an overinflated balloon. The walls get thin, the chamber expands, and the muscle loses its strength. Instead of squeezing hard to push blood out, it just flops around. Ejection fraction drops below 40%-meaning less than half the blood in the chamber is being pumped out with each beat. Normal is 55-70%.

This isn’t just about size. The heart’s electrical system often gets messy too, leading to dangerous arrhythmias. About 25-35% of cases are inherited, usually from mutations in genes like TTN (titin) or LMNA. These genes help build the heart’s internal scaffolding. When they break, the muscle literally falls apart over time.

But genetics aren’t the only cause. Heavy alcohol use-more than 80 grams a day for five years or more-can directly poison heart cells. Chemotherapy drugs like doxorubicin, especially at high cumulative doses, are another known trigger. Viral infections, like coxsackievirus, can trigger inflammation that turns chronic. Autoimmune diseases like sarcoidosis can infiltrate the heart and scar it from within.

Diagnosis starts with an echocardiogram. If the left ventricle is larger than 55 mm in men or 50 mm in women, and the ejection fraction is below 45%, DCM is likely. Cardiac MRI adds detail, showing scar tissue (fibrosis) that’s invisible on echo. Genetic testing is recommended if there’s a family history-because if one person has it, their siblings or children might too.

Treatment is standardized but powerful. The combo of sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto), a beta-blocker like carvedilol, and an SGLT2 inhibitor like dapagliflozin reduces death risk by 30% over three years. These drugs don’t fix the muscle, but they slow the damage and reduce fluid buildup. For those who don’t respond, a pacemaker or defibrillator may be needed. In advanced cases, a heart transplant is the last option-and it’s often the only one that works long-term.

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: The Heart That Grows Too Thick

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is the opposite problem. The heart doesn’t stretch-it thickens. Walls that should be 8-10 mm thick become 15 mm or more, often in just one spot: the septum, the wall between the left and right ventricles. This isn’t from high blood pressure or athletic training. It’s genetic. About 60% of cases come from mutations in sarcomere genes like MYH7 or MYBPC3, which control how heart muscle contracts.

What makes HCM dangerous isn’t just the thickness-it’s how it disrupts blood flow. In 70% of cases, the thickened septum blocks the outflow tract, forcing the heart to pump harder just to get blood out. This is called obstructive HCM. Even in non-obstructive cases, the thick muscle doesn’t relax properly, so the heart can’t fill with blood between beats. That’s diastolic dysfunction-your heart can squeeze, but it can’t refill.

HCM is the top cause of sudden cardiac death in young athletes under 35. In the U.S., it’s responsible for 36% of those tragedies. Why? During intense exercise, the blocked outflow tract worsens, and abnormal heart rhythms can kick in. Many people don’t know they have it until it’s too late.

Diagnosis relies on echocardiography and cardiac MRI. If the wall thickness is 15 mm or more (or 13 mm with a family history), and no other cause like hypertension is found, HCM is confirmed. Genetic testing identifies the mutation in about 60% of cases. A 17-gene panel costs $1,200-$2,500 in the U.S., but it’s critical for screening relatives.

Treatment focuses on reducing symptoms and preventing sudden death. Beta-blockers like metoprolol help the heart relax and slow the rate, improving symptoms in 70% of patients. For those with severe obstruction, disopyramide can reduce the blockage. But for the worst cases, a procedure called septal reduction therapy-either surgically removing part of the septum or using alcohol to destroy it-can instantly improve blood flow. About 85% of patients report major symptom relief after this.

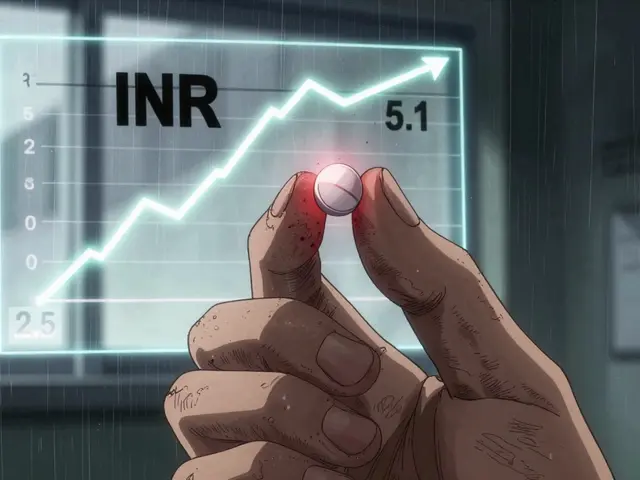

And now, there’s a new drug: mavacamten (Camzyos). Approved in 2022, it targets the root cause-overactive heart muscle contraction. In trials, it reduced the outflow tract gradient by 80%. But it’s expensive-$145,000 a year-and requires strict monitoring for low heart function.

Prognosis is good for most. Non-obstructive HCM patients have a 95% five-year survival rate. Obstructive cases drop to 70%, but with proper management, many live full lives. The key is early detection. Athletes, especially those with fainting spells or family history, should get screened.

Restrictive Cardiomyopathy: The Heart That Won’t Fill

Restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM) is rare-only 5% of cases-but it’s the hardest to diagnose and treat. The heart doesn’t get big or thick. It looks normal on echo. But it’s stiff. Like a rubber band that’s lost its stretch, it can’t relax enough to fill with blood. The result? The heart can still squeeze hard (ejection fraction stays above 50%), but not enough blood gets in. So, pressure builds up in the lungs and veins, causing swelling, fatigue, and shortness of breath-even at rest.

RCM isn’t about the muscle itself. It’s about what’s invading it. In 60% of cases, it’s amyloidosis-abnormal proteins (light chains) build up in the heart tissue, making it rigid. Sarcoidosis, hemochromatosis (iron overload), and Fabry disease (a rare genetic storage disorder) are other common causes. These aren’t heart diseases first-they’re systemic diseases that happen to wreck the heart.

Diagnosis is tricky. Echocardiography shows a classic pattern: a fast, sharp filling wave (E/A ratio >2) with a very short deceleration time (<150 ms). But the real clue is in cardiac MRI. It shows late gadolinium enhancement-not in the coronary pattern like a heart attack, but scattered across the muscle. Extracellular volume over 35% confirms fibrosis. Often, a biopsy is needed to see the amyloid deposits under the microscope.

There’s no cure for RCM itself. Treatment targets the root cause. For amyloidosis, drugs like tafamidis stabilize the protein and slow progression. In the ATTR-ACT trial, it improved walking distance by 25 meters and cut death risk by 30%. But it costs $225,000 a year. For hemochromatosis, regular blood removal (phlebotomy) can reverse damage if caught early. For sarcoidosis, steroids or immunosuppressants may help.

But here’s the brutal truth: RCM has the worst prognosis. Five-year survival is only 30-50%, depending on the cause. Amyloidosis patients, especially those with advanced disease, often die within two years without treatment. Many are misdiagnosed as having heart failure from high blood pressure or aging. One patient on Reddit said it took five doctors and three years to get the right diagnosis.

Heart transplant is often the only long-term option, but it’s risky-many patients are too frail by the time they’re listed. The key is early detection. If you have unexplained heart failure, normal ejection fraction, and no high blood pressure, ask about RCM. A simple blood test for NT-proBNP and a cardiac MRI can point the way.

Why the Classification Matters

Doctors used to group all heart muscle diseases together. That changed in the 2000s when researchers realized that treatment depends entirely on the type. You don’t treat amyloidosis the same way you treat a genetic thickening of the heart. You don’t give a beta-blocker to someone with a dilated, floppy heart the same way you give it to someone with a stiff, thick one.

Today, classification guides everything: who gets genetic testing, who needs a defibrillator, who qualifies for a transplant, and which drugs to use. The American Heart Association now says ‘ischemic cardiomyopathy’ isn’t a true cardiomyopathy-it’s heart failure caused by blocked arteries. That’s a separate category. This precision saves lives.

But gaps remain. Only 35% of community hospitals correctly classify cardiomyopathy types. Many rural areas don’t have specialists who can read cardiac MRIs or interpret genetic results. And for RCM, the lack of awareness means delays of years-costing precious time.

What You Can Do

If you have a family history of sudden cardiac death, unexplained heart failure, or known genetic heart disease, get screened. An echocardiogram is non-invasive and cheap. If you’re over 40 and have unexplained fatigue, swelling in your legs, or shortness of breath with minimal effort, don’t assume it’s aging. Ask your doctor about cardiomyopathy.

For those already diagnosed: follow your treatment plan. Take your meds. Don’t skip appointments. Monitor your weight daily-gaining two pounds overnight could mean fluid buildup. Avoid alcohol if you have DCM. If you have HCM, avoid intense competitive sports. For RCM, treat the root cause aggressively.

Research is moving fast. CRISPR gene editing is entering trials for HCM. New blood tests are being developed to spot amyloidosis before symptoms appear. The goal isn’t just to manage the disease-it’s to stop it before it starts.

Can you have cardiomyopathy without symptoms?

Yes. Many people with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, especially younger adults, have no symptoms until they collapse during exercise. Dilated cardiomyopathy can also be silent for years. That’s why family screening is critical-if one person is diagnosed, close relatives should get an echocardiogram even if they feel fine.

Is cardiomyopathy hereditary?

About 30-40% of dilated and 60% of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy cases are inherited. Restrictive cardiomyopathy is less often genetic, except in cases like Fabry disease or familial amyloidosis. Genetic testing can identify mutations, and if one is found, first-degree relatives should be screened every 3-5 years.

Can exercise cause cardiomyopathy?

Intense endurance exercise can cause temporary changes in the heart, but true cardiomyopathy from exercise alone is rare. However, in people with undiagnosed HCM, intense activity can trigger sudden death. That’s why athletes with fainting spells or family history need screening. On the other hand, heavy alcohol use over years is a direct cause of dilated cardiomyopathy.

What’s the difference between restrictive cardiomyopathy and constrictive pericarditis?

They look nearly identical on echo-both have stiff hearts and poor filling. But constrictive pericarditis is caused by a thickened, scarred sac around the heart (the pericardium), not the heart muscle itself. The treatment is completely different: surgery to remove the sac fixes constrictive pericarditis, but does nothing for restrictive cardiomyopathy. Cardiac MRI and biopsy are needed to tell them apart.

Can cardiomyopathy be reversed?

In some cases, yes. If dilated cardiomyopathy is caused by alcohol or chemotherapy and those triggers are removed early, the heart can partially recover. In hemochromatosis-related restrictive cardiomyopathy, regular phlebotomy can reverse stiffness. But for genetic forms like HCM or most DCM, the damage is permanent-treatment slows decline, but doesn’t cure it.

Cardiomyopathy isn’t a death sentence. With early detection, proper classification, and modern treatments, many people live full, active lives. The key is knowing which type you have-and making sure your doctor does too.

Jake Rudin

19 Jan 2026 at 02:20Cardiomyopathy isn’t just a medical term-it’s a silent thief. It steals rhythm, steals breath, steals futures. And yet, we treat it like a footnote in a textbook. Dilated? It’s the body’s slow collapse. Hypertrophic? A ticking bomb disguised as an athlete’s heart. Restrictive? The heart becomes a marble-perfect shape, no give. We fix symptoms, not systems. We screen for cholesterol, not titin mutations. We’re treating the shadow, not the light.