Fentanyl Patch Exposure Risk Calculator

Using a fentanyl patch might seem simple-stick it on your skin, and it slowly releases pain relief for three days. But behind that quiet adhesive is a powerful drug that can turn deadly if not handled with extreme care. Fentanyl is 50 to 100 times stronger than morphine. Even a small amount left on a used patch can kill a child or someone who’s never taken opioids before. This isn’t a hypothetical risk-it’s a documented danger that has led to over 30 pediatric deaths in the U.S. alone between 1997 and 2012.

How Fentanyl Patches Work (And Why That’s Dangerous)

Fentanyl patches are designed for people with severe, ongoing pain-like from advanced cancer or serious injuries-who need constant pain control. Unlike pills that spike and drop in your system, these patches deliver a steady stream of fentanyl through your skin over 72 hours. That sounds ideal, right? But it’s also why they’re so risky. The patch doesn’t start working right away. It takes 12 to 24 hours to reach full strength. If you take extra pain pills while waiting, you could accidentally overdose. And once the drug is in your system, it stays there. Even after you remove the patch, fentanyl keeps leaking into your bloodstream for hours. That’s why you can’t just stop using them cold turkey. Heat makes things worse. A hot shower, a heating pad, or even a fever can cause your body to absorb fentanyl faster. In some cases, this has led to fatal overdoses. The FDA warns against using these patches if you have a fever or plan to be near heat sources. Your skin isn’t just a passive surface-it’s a gateway that can turn safe use into a life-threatening event.Overdose: The Silent Killer

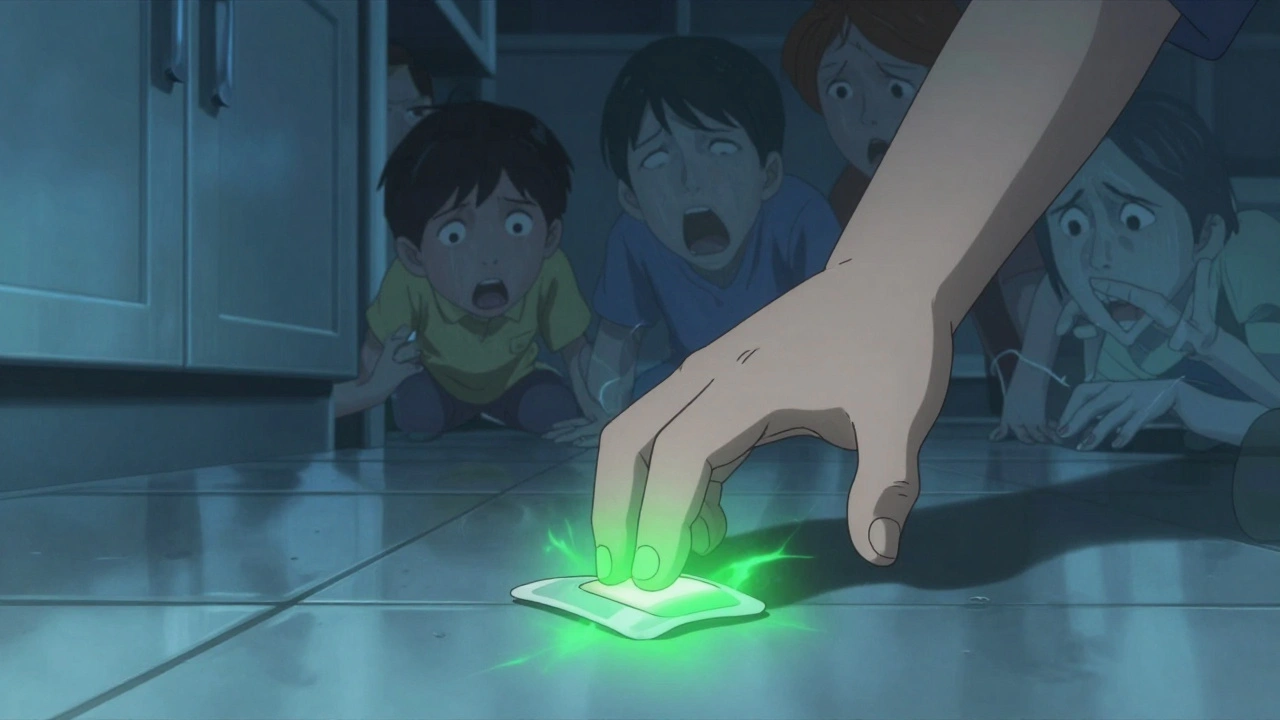

Fentanyl overdose doesn’t look like a movie scene. There’s no screaming or collapsing. It’s quiet. You might notice someone is unusually sleepy, hard to wake up, or breathing slowly-so slowly their lips turn blue. Their skin feels cold and clammy. Their pupils shrink to pinpoints. They might snore loudly, or not breathe at all. These signs aren’t rare. The FDA reports that between 2012 and 2017, 148 people suffered severe harm or died from sudden opioid withdrawal, and hundreds more from accidental exposure. Children have died after touching a discarded patch. Adults have overdosed after using someone else’s patch. Even a single used patch left on the floor can be lethal. If you or someone else shows these symptoms, act immediately:- Remove the patch right away.

- Call emergency services (911 or local equivalent).

- If you have naloxone (Narcan), give it as directed. Naloxone can reverse the overdose, but it may wear off before the fentanyl does, so you still need medical help.

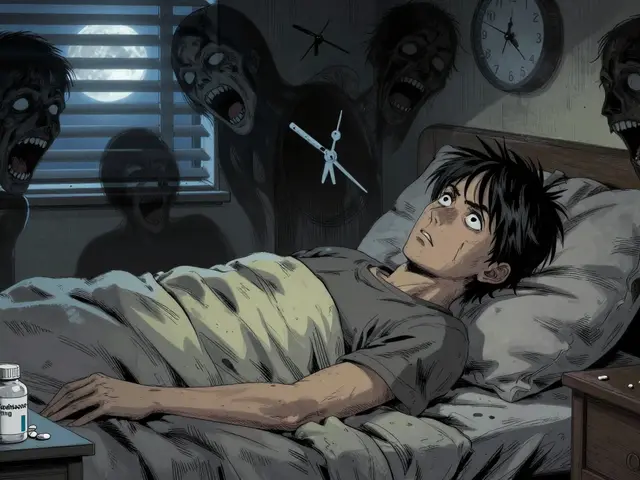

Withdrawal: When Stopping Becomes a Nightmare

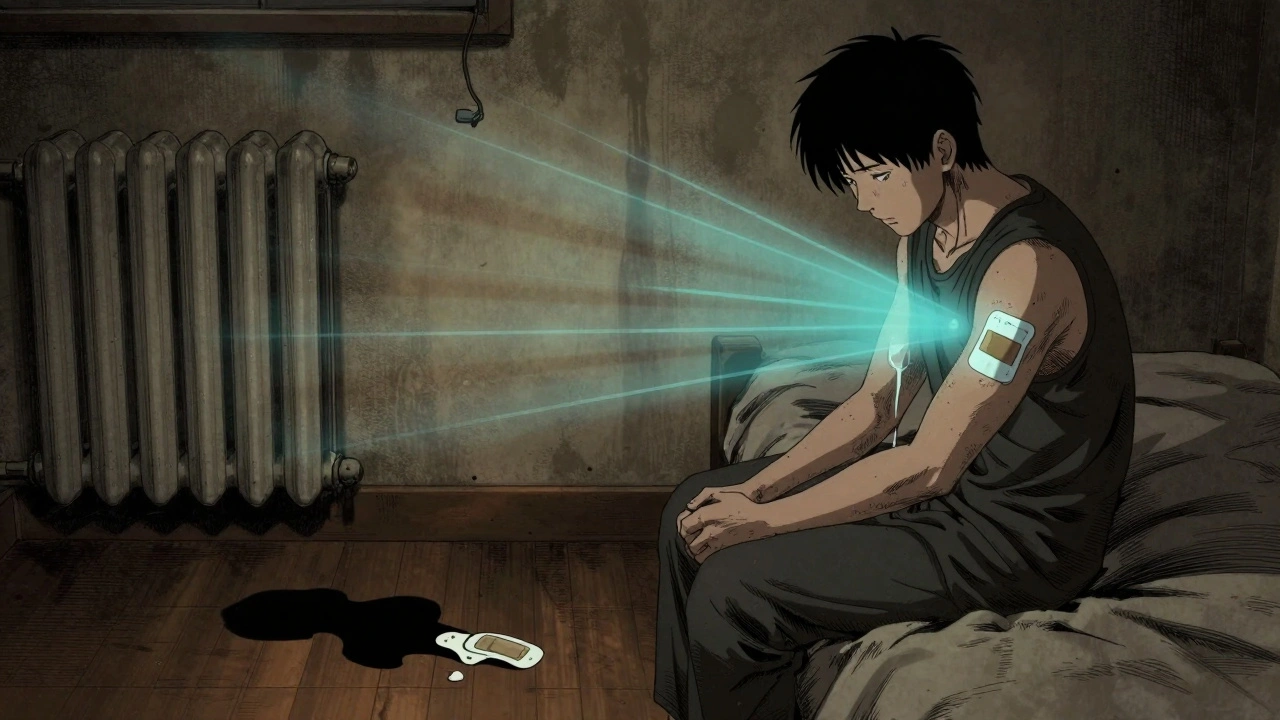

If you’ve been using fentanyl patches for more than a few weeks, your body becomes physically dependent. That doesn’t mean you’re addicted-it means your brain and nerves have adjusted to the drug. Stop suddenly, and your body goes into chaos. Withdrawal symptoms start within 8 to 24 hours after your last patch. They peak at 36 to 72 hours and can last up to 10 days. Some people feel them for weeks. Symptoms include:- Intense anxiety and irritability

- Excessive sweating, chills, and goosebumps

- Severe muscle aches and cramps

- Nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea

- Rapid heartbeat, high blood pressure

- Insomnia and restless legs

- Depression and thoughts of suicide

How to Stop Safely: The Only Way Out

There’s no safe way to quit fentanyl patches on your own. You must work with your doctor to taper slowly. A typical plan reduces your dose by 10% to 25% every 1 to 3 weeks. If you’re on a high dose, it might take months. Your doctor might switch you to a different opioid with a shorter half-life, like oxycodone, to make tapering easier. They’ll monitor your symptoms, adjust your plan, and may prescribe medications to help with nausea, anxiety, or sleep. Never cut the patch, fold it, or try to speed up the process. Don’t skip doses to “get clean” faster. That’s how people end up in the ER-or worse.What You Must Do Every Day

If you’re using fentanyl patches, these steps aren’t optional-they’re life-saving:- Store patches safely. Keep them out of reach of children and pets. Store them in a locked box, not a medicine cabinet.

- Dispose of used patches properly. Fold the sticky side over itself so it sticks to itself. Flush it down the toilet or take it to a drug take-back program. Never throw it in the trash where someone might find it.

- Avoid heat. No hot tubs, saunas, heating pads, or sunbathing. Even a warm room can increase absorption.

- Never share patches. Even if someone else has chronic pain, this drug can kill them.

- Carry naloxone. If your doctor prescribes it, keep it with you at all times. Teach a family member how to use it.

- Tell every doctor and dentist you see. Even for a tooth extraction or surgery, fentanyl can interact with anesthesia and other drugs.

Why Doctors Are Using These Patches Less

Between 2016 and 2022, fentanyl patch prescriptions in the U.S. dropped by 42%. Why? Because doctors now know the risks better. The CDC says fentanyl patches should only be used for people already tolerant to opioids-meaning they’ve been taking at least 60 mg of morphine daily for a week or more. They’re not for new patients, not for acute pain, and not for “as-needed” use. In 2023, 78% of doctors said they only consider fentanyl patches after all other pain treatments have failed. That’s up from 52% in 2016. The FDA now requires prescribers to be trained in opioid safety, and many pharmacies won’t fill the prescription unless you’ve had a recent check-up.What’s Next for Fentanyl Patches?

Researchers are working on safer versions. Two clinical trials are testing new patch designs that stop releasing fentanyl if the patch is tampered with or exposed to heat. These aren’t on the market yet, but they could change how we think about long-term pain treatment. For now, the message is clear: fentanyl patches have a place in pain care-but only for a small group of patients, under strict supervision. The risks aren’t just possible. They’re predictable. And they’re preventable-if you know how to use them, and how to stop.Can fentanyl patches be used for short-term pain like after surgery?

No. Fentanyl patches are not approved for acute, post-surgical, or short-term pain. They take 12 to 24 hours to start working and last for 72 hours. If you need quick pain relief after surgery, other medications like IV opioids or short-acting pills are safer and more effective. Using a patch for sudden pain increases overdose risk because you can’t adjust the dose quickly.

Is it safe to cut a fentanyl patch to lower the dose?

Never cut, chew, or alter a fentanyl patch. The patch is designed to release medication slowly through a special membrane. Cutting it destroys that control and can cause a dangerous surge of fentanyl into your body. This has led to multiple overdose deaths. Always use the exact dose your doctor prescribes.

How long does fentanyl stay in your system after removing the patch?

Fentanyl can remain in your bloodstream for up to 24 hours after removing the patch, even though the patch stops delivering the drug. This is why you can’t stop abruptly-you’re still getting a dose from what’s stored in your skin and fat. That’s also why withdrawal symptoms can take hours to appear. The drug lingers, and your body needs time to adjust.

Can I drink alcohol while using a fentanyl patch?

No. Alcohol combined with fentanyl can slow your breathing to a dangerous level-even if you’ve used opioids before. The FDA warns that mixing alcohol with fentanyl patches can cause fatal respiratory depression. This includes beer, wine, and any product containing alcohol, like mouthwash or cough syrup. Avoid it completely while using the patch and for at least 24 hours after removing it.

What should I do if I miss a patch change?

If you miss a patch change by less than 12 hours, apply a new one as soon as you remember. If you’re more than 12 hours late, skip the missed dose and apply the next patch at your regular time. Do not apply an extra patch to make up for it. Missing doses can trigger withdrawal symptoms, but doubling up can cause overdose. Always talk to your doctor if you’re having trouble sticking to the schedule.

Are there alternatives to fentanyl patches for chronic pain?

Yes. Many people manage chronic pain with non-opioid options like gabapentin, physical therapy, nerve blocks, or low-dose antidepressants. If opioids are needed, shorter-acting pills like oxycodone or morphine are often safer because you can adjust the dose daily. Fentanyl patches are only considered when other treatments have failed and your pain is severe and constant. Always ask your doctor about alternatives before starting a patch.

Michael Feldstein

5 Dec 2025 at 09:20I’ve been on these patches for two years after my back surgery went sideways. People don’t get how scary it is to be stuck with something that can kill you if you sneeze wrong. But honestly? It’s the only thing that lets me play with my kids without crying. Just gotta be hyper-vigilant - no heat, no alcohol, and I fold my used ones like a ninja.