Drinking alcohol while taking prescription meds might seem harmless-maybe you had one glass of wine with dinner, or a beer after work. But if you’re on certain medications, that drink could be life-threatening. It’s not just about feeling drowsy. This isn’t a myth. It’s a medical reality backed by data from the CDC, FDA, and top health organizations. In 2022 alone, alcohol-drug interactions contributed to 2,318 overdose deaths in the U.S. And most people have no idea they’re at risk.

Why Alcohol and Prescription Drugs Don’t Mix

Alcohol doesn’t just sit there quietly in your body. It actively interferes with how your medications work. There are two main ways this happens: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interactions.Pharmacokinetic means alcohol changes how your body processes the drug. Most medications, including painkillers, antidepressants, and blood thinners, are broken down by liver enzymes-especially the CYP450 family. Alcohol can either speed up or slow down these enzymes. Chronic drinkers (more than 14 drinks a week for men, 7 for women) trigger enzyme overactivity, making drugs like propranolol less effective by up to 50%. On the flip side, having even one drink right before taking a medication can block those same enzymes, causing the drug to build up to dangerous levels in your blood. One study showed alcohol increased warfarin levels by 35%, raising the risk of internal bleeding.

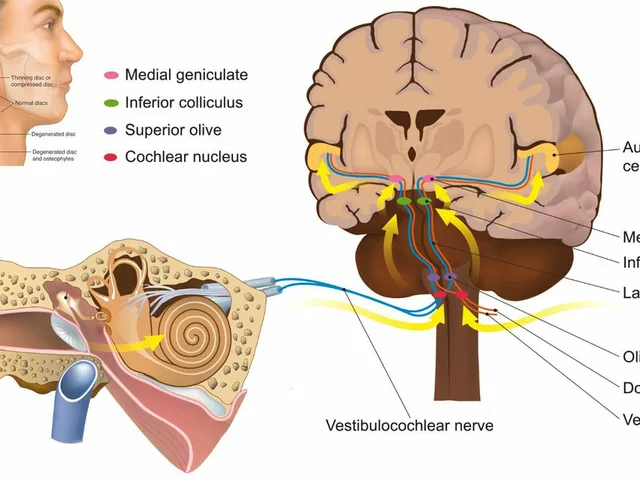

Pharmacodynamic interactions are even scarier. This is when alcohol and the drug amplify each other’s effects. Think of it like stacking two heavy weights on a scale. Both alcohol and benzodiazepines (like Xanax or Valium) depress your central nervous system. Together, they don’t just add up-they multiply. Research shows combining alcohol with diazepam increases sedation by 400%. That’s not just feeling sleepy. That’s slowed breathing, loss of coordination, blackouts, and even coma.

High-Risk Medications: What to Avoid with Alcohol

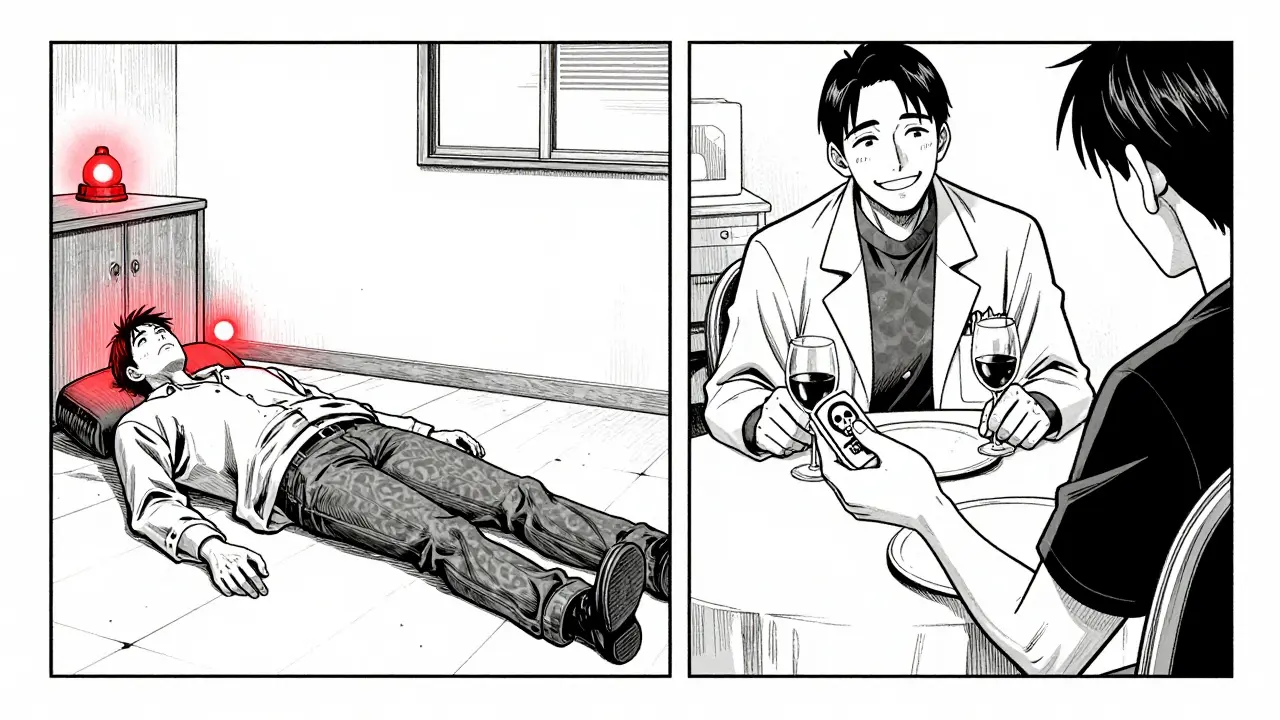

Some medications are okay with occasional alcohol. Others? Never mix them. Here’s what you need to watch out for:- Opioids (oxycodone, hydrocodone, morphine): Alcohol + opioids = 6x higher risk of fatal respiratory depression. Even one drink with a therapeutic opioid dose doubles your chance of a deadly car crash. These combinations caused 26% of all prescription drug overdose deaths in 2022.

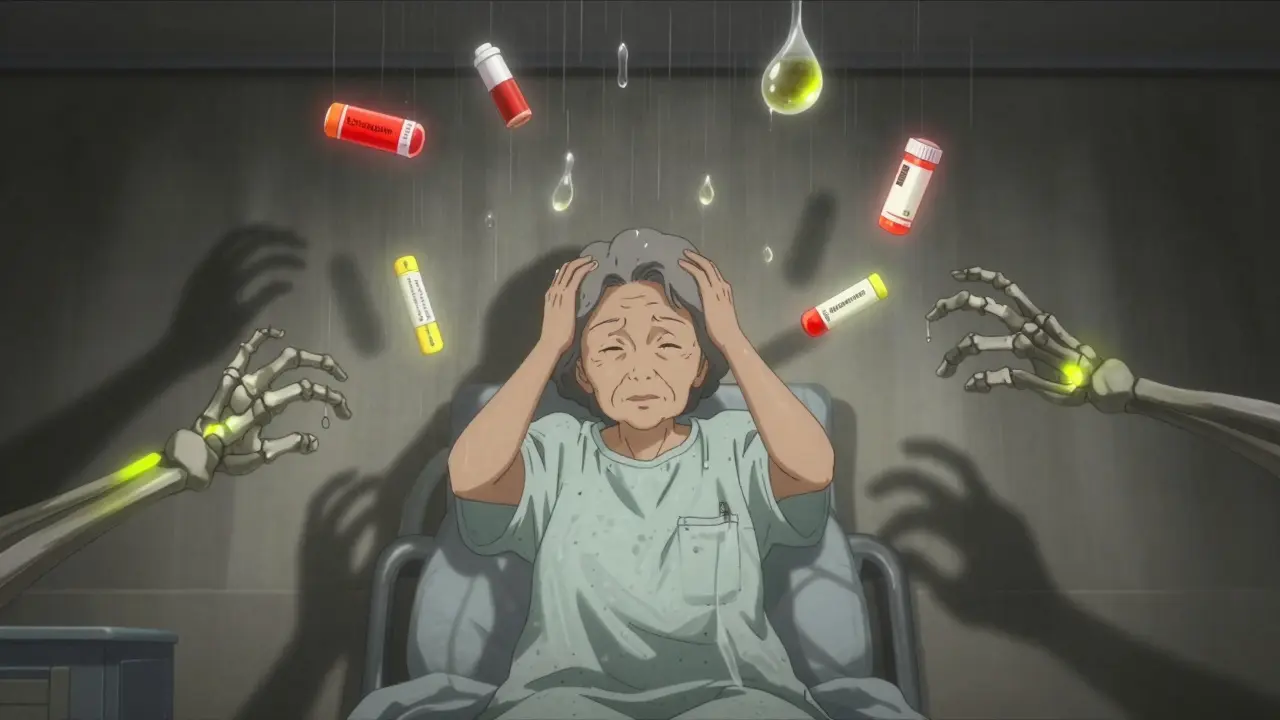

- Benzodiazepines (alprazolam, lorazepam, diazepam): These are prescribed for anxiety or insomnia. But with alcohol, they turn your brain into a slow-motion shutdown. Falls in older adults increase by 50%. Emergency rooms see this daily.

- Antidepressants (SSRIs like sertraline, fluoxetine): You might think it’s safe because they’re not sedating. But 35% of adults over 65 experience extreme drowsiness when mixing alcohol with SSRIs. That’s enough to cause a fall, a fracture, or worse.

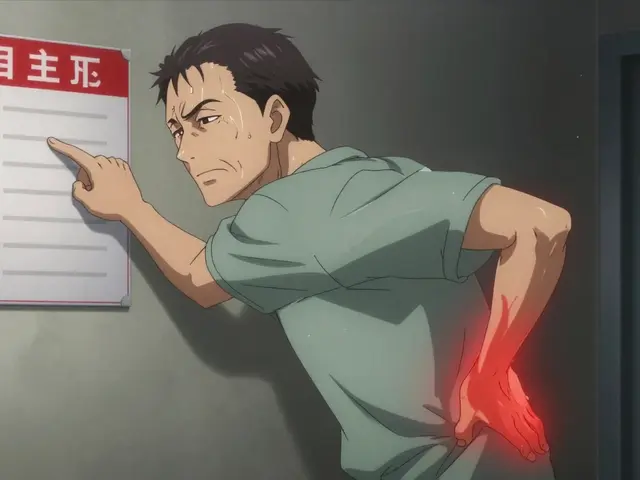

- NSAIDs (ibuprofen, naproxen): These painkillers already irritate your stomach lining. Add alcohol, especially heavy drinking (3+ drinks/day), and your risk of internal bleeding skyrockets by 300%.

- Acetaminophen (Tylenol): Even a few drinks a day with regular Tylenol use can trigger acute liver failure. The FDA estimates 1 in 200 regular users develop this. It’s silent, sudden, and often fatal.

- Antibiotics (isoniazid, metronidazole): Most antibiotics don’t interact, but isoniazid (used for TB) causes severe liver damage in 15% of people who drink. Metronidazole causes vomiting, flushing, and rapid heartbeat when mixed with alcohol.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Not everyone reacts the same way. Age, gender, and health conditions change your risk dramatically.Adults over 65 are the most vulnerable. Their livers process alcohol and drugs slower. They’re also more likely to be on multiple prescriptions. Studies show they experience 3.2 times more severe interactions than younger adults. The American Geriatrics Society lists 15 alcohol-interacting drugs as inappropriate for seniors. And 78% of falls in nursing homes linked to sedatives happened when the person had alcohol within six hours.

Women face higher risks too. On average, they have less body water and more body fat. That means alcohol stays concentrated in their bloodstream longer. A drink that’s safe for a man might be dangerous for a woman of the same weight.

If you have liver disease, diabetes, or heart problems, your body is already under stress. Adding alcohol to the mix? It’s like pouring gasoline on a fire. Liver patients have a 5-fold higher risk of acetaminophen toxicity when drinking-even moderate amounts.

What Patients Don’t Know (And Why It’s Deadly)

Here’s the worst part: most people aren’t warned.A review of 12,450 patient reviews on Healthgrades found that 68% were never told they shouldn’t drink while on benzodiazepines. One Reddit user shared how he was prescribed oxycodone after wisdom teeth surgery. He had two beers. Within minutes, he couldn’t breathe. He sat there, panicked, for 20 minutes before his roommate called 911. He survived. Others don’t.

WebMD’s 2023 survey of 5,842 adults showed 57% believe “one drink is safe with most medications.” Thirty-two percent think only hard liquor causes problems. That’s not just ignorance-it’s dangerous misinformation.

Even healthcare providers miss it. A 2023 study in JAMA Internal Medicine found 43% of primary care doctors couldn’t correctly identify all high-risk medication classes. And only 38% of benzodiazepine prescriptions include explicit alcohol warnings on the label.

What You Should Do

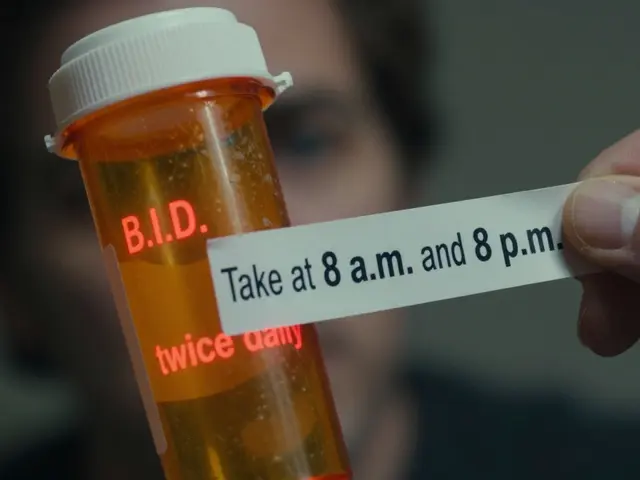

You don’t need to be a doctor to protect yourself. Here’s what works:- Check the label. Look for “Do not consume alcohol” or “Avoid alcohol.” But don’t rely on this-only 65% of high-risk prescriptions include the warning.

- Ask your pharmacist. Pharmacists are trained to catch these interactions. Use the 4-question screening tool: “Do you drink alcohol? How much? How often? When did you last drink?” This method has 92% sensitivity in catching risky combinations.

- Use the NIAAA’s free app. The “Alcohol Medication Check” app lets you scan your prescription barcode or search by name. It cross-references over 2,300 medications and tells you your risk level: red (dangerous), yellow (caution), green (low risk).

- Be honest with your doctor. If you drink-even one glass of wine a night-say so. Don’t assume it’s irrelevant. Your doctor needs to know to adjust your meds or suggest alternatives.

Some pharmacies are already doing this right. One patient on Google Reviews wrote: “My Walgreens pharmacist refused to fill my lorazepam prescription when I admitted to regular drinking. Probably saved my life.” That’s not overreach-that’s responsible care.

The Future Is Here

Technology is catching up. In 2024, Epic Systems rolled out AI tools that analyze 200+ patient variables-age, liver enzymes, drinking habits, other meds-to predict individual interaction risk with 89% accuracy. Hospitals using these systems cut alcohol-related adverse events by 28%.The FDA now requires explicit “ALCOHOL WARNING” labels on high-risk prescriptions. The CDC’s 2023-2025 plan aims to cut overdose deaths by 50% through mandatory provider training. Forty-two states now require continuing education on drug-alcohol interactions for doctors to renew their licenses.

But tech alone won’t fix this. A 2023 study in Annals of Internal Medicine found only 28% of high-risk patients actually stop drinking-even after being warned. The real challenge isn’t knowledge. It’s behavior.

Final Reality Check

If you’re on opioids, benzodiazepines, or any sedating medication, the safest choice is zero alcohol. No exceptions. No “just one.” The science is clear. The deaths are real. The warnings are there-if you know where to look.For everything else-antibiotics, blood pressure meds, thyroid pills-check with your pharmacist. Don’t guess. Don’t assume. Don’t risk it.

Your body doesn’t have a “safe amount” for mixing alcohol and prescription drugs. It has one rule: if it’s not on the label, ask. And if the answer is uncertain? Skip the drink. Your life isn’t worth the gamble.

Can I have one drink with my prescription medication?

It depends on the medication. For opioids, benzodiazepines, or sleep aids, even one drink can be deadly. For some antibiotics or blood pressure drugs, one drink may be low risk-but only if you’re healthy and not taking multiple meds. The safest approach is to check with your pharmacist before drinking anything. Never assume it’s safe.

What should I do if I accidentally mixed alcohol with my medication?

If you feel dizzy, extremely sleepy, have trouble breathing, or feel confused, call emergency services immediately. Don’t wait. Alcohol and drug interactions can worsen quickly. If you’re not having symptoms but are worried, contact your pharmacist or doctor right away. They can assess your risk based on the medication, how much you drank, and your health history.

Do over-the-counter meds like Tylenol interact with alcohol?

Yes. Acetaminophen (Tylenol) combined with alcohol-even moderate daily drinking-can cause severe liver damage. The risk is highest if you drink regularly and take Tylenol often. The FDA warns that 1 in 200 regular users develop acute liver failure this way. Avoid alcohol entirely if you use Tylenol more than a few times a week.

Why don’t doctors always warn patients about alcohol interactions?

Many doctors assume patients know, or they’re rushed during appointments. Only 38% of benzodiazepine prescriptions include alcohol warnings on the label. A 2023 study found 43% of primary care physicians couldn’t correctly identify all high-risk medications. It’s not always negligence-it’s a system failure. That’s why you need to ask. Don’t wait for them to tell you.

Is it safe to drink the day before or after taking medication?

It depends on the drug’s half-life. Some medications stay in your system for days. For example, diazepam (Valium) can linger for over 48 hours. Alcohol consumed the night before can still interact the next day. If you’re on a high-risk medication, avoid alcohol entirely-not just on the day you take it. When in doubt, skip it.

Can I switch to a different medication to avoid alcohol interactions?

Sometimes, yes. For example, if you’re on a benzodiazepine for anxiety and drink regularly, your doctor might switch you to a non-sedating antidepressant like sertraline. Or if you’re on an NSAID for pain, they might suggest physical therapy or a different painkiller. Always discuss alternatives with your doctor-don’t stop or change meds on your own.

Guillaume VanderEst

17 Dec 2025 at 12:58Just had my pharmacist flat-out refuse to fill my Xanax script after I mentioned I had a glass of wine with dinner. Said, 'I don't care if it's one sip - you're one bad night away from not waking up.' Walked out feeling like a criminal, but also... kinda grateful?

Never thought I'd say this, but my pharmacist is my new hero.