Immunosuppression Infection Risk Calculator

Personal Risk Assessment

This tool estimates your risk of unusual infections based on your immunosuppression type and treatment duration. Remember: Infections in immunosuppressed patients often present without fever or obvious symptoms. Early detection is critical.

When your immune system is turned down-whether by steroids, chemotherapy, transplant drugs, or autoimmune treatments-you’re not just more prone to colds. You’re at risk for infections that most people never even hear about. These aren’t your typical flu bugs or strep throats. They’re rare, aggressive, and often silent until it’s too late. A person on long-term prednisone might brush off a cough as seasonal allergies. But that cough could be Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia, a fungus that only thrives when your T-cells are wiped out. And if you don’t catch it early, the survival rate drops fast.

Why Normal Infections Act Totally Different

In healthy people, infections scream for attention. Fever. Swelling. Pus. Redness. Your body fights back loudly. But in someone on immunosuppressants, that fight is muted. The immune system doesn’t just weaken-it forgets how to signal danger. That’s why a simple skin rash might be histoplasmosis spreading under the surface. Or a mild headache could be Toxoplasma gondii attacking the brain. No fever. No swelling. Just quiet, creeping damage.Studies show that up to 23% of immunosuppressed patients with confirmed infections show zero symptoms at all. One child with severe combined immunodeficiency had Pneumocystis in their lungs but no cough, no fever, no trouble breathing. They were found during a routine scan. By the time symptoms appear, the infection is often advanced. That’s why doctors don’t wait for signs-they test early and often.

Who’s at Risk for What?

Not all immunosuppression is the same. The type of drug, the condition being treated, and the level of immune suppression each shape which bugs can slip in.- Humoral defects (low antibodies): These patients struggle with Giardia intestinalis, a parasite that causes chronic diarrhea, bloating, and weight loss. In healthy people, it clears in weeks. In someone with IgA deficiency, it can last for months, even years. Treatment often needs higher doses or longer courses because the body can’t clear it on its own.

- T-cell deficiency (common after transplants or with drugs like cyclosporine): This is where viruses take over. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivates in up to 40% of transplant patients without prophylaxis. Adenovirus and HHV-6 can cause deadly lung or liver damage. Even common cold viruses like human metapneumovirus or coronavirus NL63 can turn into pneumonia.

- Neutropenia (low white blood cells, often from chemo): This opens the door to fungi. Aspergillus is the big one. In healthy people, you breathe in spores daily. Your immune system swallows them. In a neutropenic patient, those spores grow into invasive mold that eats through lung tissue. Mortality? Over 50% even with the best antifungals.

- Phagocyte defects (like chronic granulomatous disease): These patients get hit by Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas, and Klebsiella in their skin and bones. But they also get weird ones-Flexispira species, bacteria usually found in animal guts, showing up in human infections because their immune system can’t kill them.

One of the most chilling cases from the 1960s involved a patient on immunosuppressants after a skin transplant. What looked like a bad case of erysipelas-a common bacterial skin infection-was actually histoplasmosis spreading under the skin. No one recognized it because it didn’t look like histoplasmosis. The patient died before the right diagnosis was made.

The Silent Killers: Fungi, Parasites, and Rare Bacteria

Most people think of bacteria and viruses. But in immunosuppressed patients, fungi and parasites are just as dangerous.Pneumocystis jirovecii is the most common lung infection in people with HIV or after transplants. It’s not a virus. It’s not a bacterium. It’s a fungus that lives in most of us but never causes trouble. Until your T-cells drop below 200. Then it explodes. Diagnosis? Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) is 92% accurate. Sputum? Only 65%. That’s why doctors don’t rely on coughed-up mucus-they go straight to the lungs.

Giardia doesn’t just cause diarrhea. In immunosuppressed kids, it leads to malnutrition, stunted growth, and chronic gut inflammation. Standard 5-day metronidazole courses often fail. Many need 10-day treatments or combination therapy with tinidazole. And even then, relapse is common.

Then there’s Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC). It’s everywhere-in soil, water, birds. Healthy people ignore it. But in someone on long-term steroids or after a transplant, MAC can cause fever, night sweats, weight loss, and liver damage. It’s often mistaken for TB. Culture takes weeks. By then, the infection is widespread.

And don’t forget Aspergillus. It grows on damp walls, compost piles, even air conditioning filters. In a neutropenic patient, it doesn’t just cause sinusitis-it invades blood vessels, cuts off oxygen to tissue, and spreads to the brain. Survival? Less than half, even with voriconazole or amphotericin B.

Diagnosis: When Symptoms Don’t Show Up

If you’re waiting for fever, you’re too late.Doctors rely on proactive testing. For anyone on immunosuppressants with respiratory symptoms-or even no symptoms at all-BAL is standard. For GI issues, stool tests with immunofluorescence catch Giardia in 98% of cases. Blood cultures often miss fungal infections. So they use PCR tests for CMV, Aspergillus DNA, or even metagenomic sequencing when nothing grows in culture.

One study tracked 69 kids before stem cell transplant. Nearly 40% had pathogens in their lungs, but almost a quarter showed no cough, no fever, no wheezing. They were found because someone ran the test anyway. That’s the rule now: test before you wait.

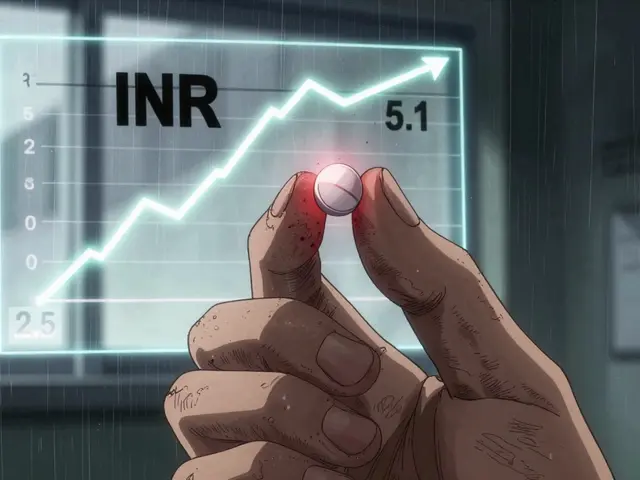

Treatment Isn’t Just About Antibiotics

You can’t just give the same dose to an immunosuppressed patient as you would to someone healthy. Their liver and kidneys process drugs differently. They’re more likely to have toxic reactions. And their bodies can’t clear the infection alone-so drugs must do more work.For Giardia, metronidazole is first-line, but 30-40% of immunosuppressed patients relapse. They need longer courses or switch to nitazoxanide. For Aspergillus, voriconazole is preferred, but if the patient’s on cyclosporine, the drug levels can spike dangerously. Dosing has to be monitored daily.

For CMV, preemptive therapy is now standard. If the virus shows up in blood tests-even with no symptoms-antivirals like ganciclovir or valganciclovir start immediately. Waiting for fever means losing the battle.

And for rare infections like MAC, treatment isn’t one drug. It’s three: azithromycin, ethambutol, and rifabutin, for months. Stopping early? That’s how drug resistance builds.

The New Threats: Pandemics and Emerging Bugs

The pandemic didn’t just change how we think about COVID. It changed how we think about all viruses in immunosuppressed people.Some patients shed SARS-CoV-2 for over 120 days. That’s more than 8 times longer than healthy people. They became long-term carriers, potentially spreading new variants. That’s why some transplant centers now screen for coronavirus every week in high-risk patients.

Even lesser-known coronaviruses like NL63 and HKU1 are now on the radar. In 2022-2023, they made up 8.5% of respiratory infections in leukemia patients. Before 2020, most doctors didn’t test for them.

Now, researchers are testing T-cell therapies-giving patients lab-grown immune cells trained to fight CMV or adenovirus. In trials, 70% of patients with treatment-resistant infections responded. It’s not standard yet, but it’s coming.

What You Need to Know

If you’re on immunosuppressants:- Don’t wait for symptoms. Routine screening saves lives.

- Report even minor changes: a new cough, a rash, unexplained fatigue, loose stools.

- Know your specific risk based on your drug and condition.

- Don’t skip vaccines-flu, pneumococcal, COVID, RSV. They’re even more important for you.

- Ask about prophylactic meds. Many patients get daily trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole to prevent PCP.

Infection in an immunosuppressed person isn’t a bug-it’s a medical emergency. And it doesn’t knock. It sneaks in. The only way to stop it is to look before it’s too late.

What are the most common unusual infections in people on steroids?

People on long-term steroids are most at risk for Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PCP), fungal infections like Aspergillus, and reactivated viruses like CMV and herpes simplex. These infections often appear without fever or obvious symptoms. PCP is the most frequent, especially if steroid use lasts more than 3 weeks at doses over 20 mg of prednisone daily.

Can you get sick from normal germs if you’re immunosuppressed?

Yes-but the problem isn’t just that you catch them easier. It’s that they behave differently. A common cold virus can turn into pneumonia. A simple skin scrape can become a deep, spreading infection. Even harmless gut bacteria like E. coli can cause bloodstream infections. Your body can’t contain them like it used to.

Why do some immunosuppressed patients have no fever during serious infections?

Fever is caused by your immune system releasing chemicals called pyrogens. When your immune system is suppressed-especially T-cells and macrophages-it can’t produce those signals. So even if bacteria or fungi are multiplying rapidly, your body doesn’t raise your temperature. That’s why doctors rely on blood tests, imaging, and cultures-not just fever-to diagnose infection.

Is it safe to travel if you’re on immunosuppressants?

Travel is possible but requires planning. Avoid areas with high rates of fungal spores (like deserts with coccidioidomycosis), untreated water (risk of Giardia), and regions with outbreaks of viruses like dengue or Zika. Get pre-travel counseling. Bring extra medication. Know where to get care abroad. Many transplant centers offer travel kits with antibiotics and emergency instructions.

Can immunosuppressed patients get vaccinated?

Yes-but not all vaccines work the same. Inactivated vaccines (flu shot, pneumococcal, COVID, HPV) are safe and recommended. Live vaccines (like MMR, varicella, nasal flu) are dangerous and should be avoided unless your immune system has fully recovered. Timing matters: vaccines are best given before starting immunosuppression or during periods of lower drug levels.

How do doctors diagnose infections when tests come back negative?

When cultures are negative but suspicion is high, doctors turn to molecular tests: PCR for viruses and fungi, antigen tests for Aspergillus or Cryptococcus, and metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS). mNGS reads all genetic material in a sample-bacteria, fungi, viruses-even ones that don’t grow in labs. It’s becoming standard in transplant centers for unexplained fevers or lung infiltrates.

Danny Nicholls

23 Nov 2025 at 19:37Bro i just got off prednisone after 6 months and honestly didn't realize how much my body was just... quiet. No fever, no nothing. Then i got a weird cough and thought it was allergies. Turned out to be PCP. 😳 Docs said if i'd waited another week, i might not be here. Never ignore a sniffle again. 🙏